Boško and Admira

- Kaja Petrovič

- Dramaturgy: Nik Žnidaršič

- Set design and video: Dorian Šilec Petek

- Costume design: Nina Čehovin

- Music and sound: Gašper Lovrec

- Lighting design: Andrej Hajdinjak

- Language consultant: Mateja Dermelj

- Graffiti: Dorijan Šiško

- Stage manager: Urša Červ

The starting point of the project is a wartime photo of a dead couple, embraced, on the Vrbanja Bridge. The Muslim Admira Ismić and the Orthodox Boško Brkić tried to escape the occupied Sarajevo in 1993, but were shot by an unknown sniper mere metres before the border. The author of the photo, the American photographer Mark H. Milstein and the journalist Kurt Schork named the couple “Romeo and Juliet of Sarajevo” and – despite the protests of both their families – turned the tragic death of two young people from opposing sides into a sensationalist story of a young couple in love, caught in the bloody dissolution of Yugoslavia.

When analysing the photo, the creators will question war photography and their own attitude to it. And war photography, torn between glorifying wartime violence and being an essential reminder of the horrors of war, is actually in a similar position than the production will find itself. What is an ethically responsible and reasonable position of an artist in relation to the documentary materials? What right do we have to use theatre space to talk about the pain of others that we ourselves cannot understand? Isn’t the question of sensitivity and ethics often simply an excuse for social inactivity? And above all: how do we avert the next war?

I think quite a few of us are familiar with the story of Romeo and Juliet from Sarajevo. What we don’t know are the stories of thousands of other Boškos and Admiras who die in every war. In every unnecessary war. Some were named in the production. Let’s say that the story about Boško and Admira is the cause to think about the need of gun-brandishing all over this shitty planet. Everybody opened fire, but nobody fired at them. And yet, they died of a bullet. […] I must admit, this is an incredibly powerful performance, and it is not a surprise that it is sold out weeks in advance. […] Chapeau! Those who don’t see it will miss a lot. My review of the show can end with a single sentence: What the f*ck do we need war for?

This is a documentary performance that skilfully navigates the fragile balance between authenticity and artistic interpretation, without being theatrically grandiose or melodramatic. It eschews any type of moral doctrine that could easily creep into the topic, while managing – by shifting between the actual and the symbolic – to position the story of Boško and Admira in the universal and to focus not on their unwavering love that persists beyond death, but on the context of their death – war and crime. This brings the question of war photography and war reporting (and their purpose) to the forefront, researching the genre of journalism on the fine line between sensationalism and information, between exploiting tragedy for career building and earnest humanitarianism. The production deftly questions the ethics of representation and prompts us to consider how narratives of suffering are created and reproduced. In this way, the production is at the same time an homage to the victims and a critique of the systems that broadcast their stories. […] The production thus brilliantly transitions from an initial critique of pop-culture interpretations of the story, through a possible interpretation of the actual story, to the final scene where it contextualises the story in the comprehensive global structure, without ever pretending to know more than the audience, more than the people who created it. Boško and Admira emerges as Živa Bizovičar’s best work to date and certainly one of the Mladinsko’s finest productions of the last few years: it fits into the theatre’s body of work by using its familiar philosophical and theatre code, but it elevates it with sensibility, freshness and openness to possibilities beyond things we’re already sure of.

The actors frequently step beyond the stage, exiting through the front doors and even leaving the venue of Pošta (formerly Nova Pošta of Mladinsko Theatre), effectively expanding the performance space. This directorial choice is particularly interesting: when the actors disappear from our sight, we are left to rely solely on the camera projecting what unfolds beyond the wall. But can we truly trust it? Or are we naively deceived? This spatial expansion is especially powerful in a scene where Keser and Bezjak lie on the ground outside (beyond the visible stage) in the position of Boško and Admira’s bodies, and the camera projects this image onto the screen. Just a few moments later, they step onto the stage, even though the external image is still visible. And for a moment, the audience is in shock, realizing that they have just been deceived. [...] The performance feels highly dynamic. It is composed of numerous short scenes, which, due to the fast-paced rhythm, the audience struggles to fully process. At times, it can even give the audience the impression that too much is happening on stage. [...] Nevertheless, the thematic and poetic-aesthetic aspects of the performance remain very strong – especially the ending.

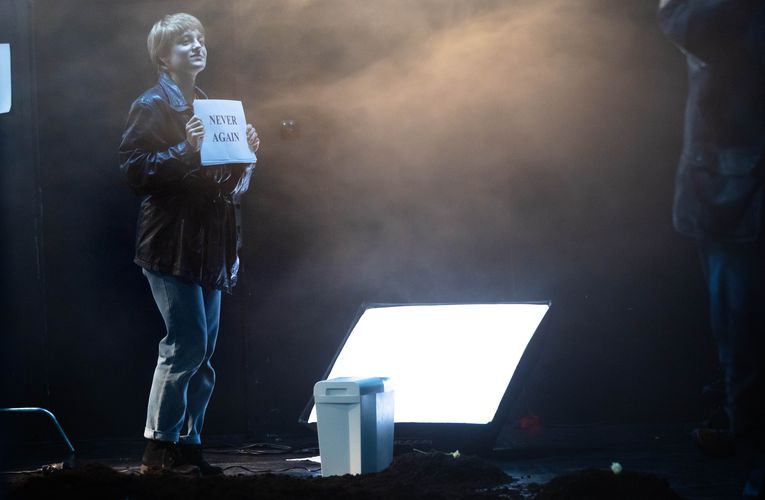

Bizovičar constructs the complexity of the play’s subject matter with responsibility and appropriate distance while also highlighting its sensationalist portrayal – for example, in the opening podcast scene – by using parody, irony and, at times, cynicism. […] The cast, consisting of Primož Bezjak, Nataša Keser, Boris Kos, Stane Tomazin and the guest Kaja Petrovič, proves to be extremely fluid in shifting through layers of expression and languages. Nina Čehovin’s costume design is based on streetwear – her signature item is a leather jacket; a prop actors use to move from one character to another. The actors infuse the production with the right dose of humour, which they then instantly swerve back to more serious tones. Similar sensitivity can be seen in the attempts to inhabit the lives of the protagonists, which nevertheless carry sensitive distance in them at all times, an underscored consciousness of performing, when, for example Tomazin and Petrovič are waking up at the beginning of the production as a young couple in love, or later, when Keser and Bezjak perform a fantasy film of the continuation of Boško’s and Admira’s life (in an extremely effective stage implementation of the film language down to using the arch of the theatre door as a film shot frame). Their transformations into different roles, to which they sometimes only lend their voices (for example, the silent parents we see on screen), and at other times also the body, underlines the decision of the creative team to fend off fantasy illusionism or further contributions to the treasure chest of mythologisation of the story.

Where are the limits of sensationalist reporting? Can we avoid war at all? Are we, throughout our entire existence, constantly trapped in the same loops? Through the touching theatre experience, Živa Bizovičar and her team raise a spectrum of questions without providing any answers. […] The ensemble is harmonious and acts like a cohesive unit. Particularly striking is Nataša Keser – be it as Amira, the Influencer, the Narrator or the abstract harbinger of death – as she portrays her characters with strong emotions and sensitivity. Her stage presence is precise and consummate in every segment of the play. […] The production opens a number of brutal truths and questions that it provides no answers to, nor does it show the ‘right’ way. It only reveals the world as it really is, trapped in cycles of repeated mistakes. Can we really change it? The artistic team devised a smart, investigative and powerful theatre piece which, using minimal interventions and sparse stage elements, takes us on a rich and sensitive journey, through the emotional, historical and metaphorical contexts.

In this fragmentary production, which tries to untangle the knots in the endless enigmatic loops of its own scenes, the spectators are sensitised to immerse into reflections on the reasons for recurring terrible anomalies in the history of human existence. It weaves together the scenarios of lived experience and perceived imagining that never came to be. Different perspectives appear through fateful contact of the intimate and the public/political, yet none of them explain the reasons for the actual crime on the Sarajevo bridge of love or for the distortions of the human mind in the broader frame of human tragedy. With the actors each having several functions, roles and interpretations, we move through theatre compositions of interiors and exteriors, we are in between the spaces of different ideologies at the threshold of freedom and captivity, in an actual geopolitical picture of the military networks of the world, on the map of a city at war, or even in a darkroom where the gaze begins to focus on the two corpses – the synonyms for countless, nameless victims of senselessness. A choir of shattering languages of harmonious and antagonistic narrations (whether textual, sound, music, video, film or photographic narratives) creates a number of associations that – just like too early graves – never end.

Marko Turk, Boštjan Videmšek